He’s a 12 year old boy and he is having problems with multiplication. Here and there he’s still adding and subtracting instead of multiplying. The timetables are not automatised yet even though this has been practised at school for years.There is a scent of dyscalculia around him. He doesn’t have much faith that this problem could be resolved. He is avoiding it as much as possible.

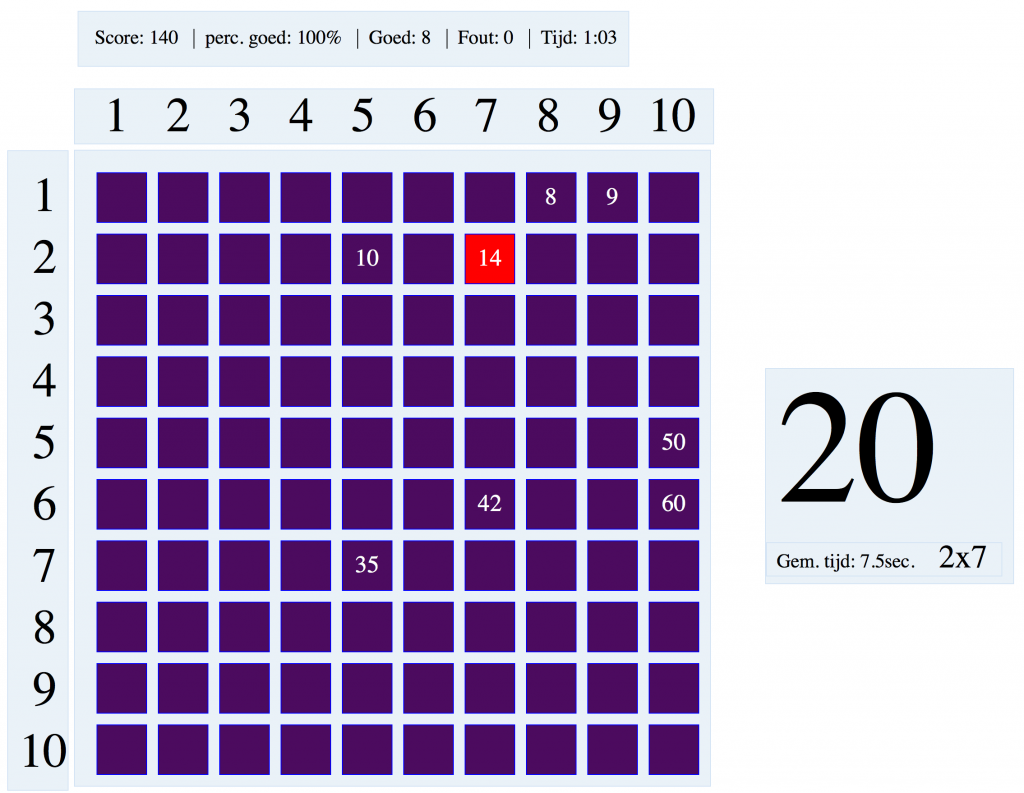

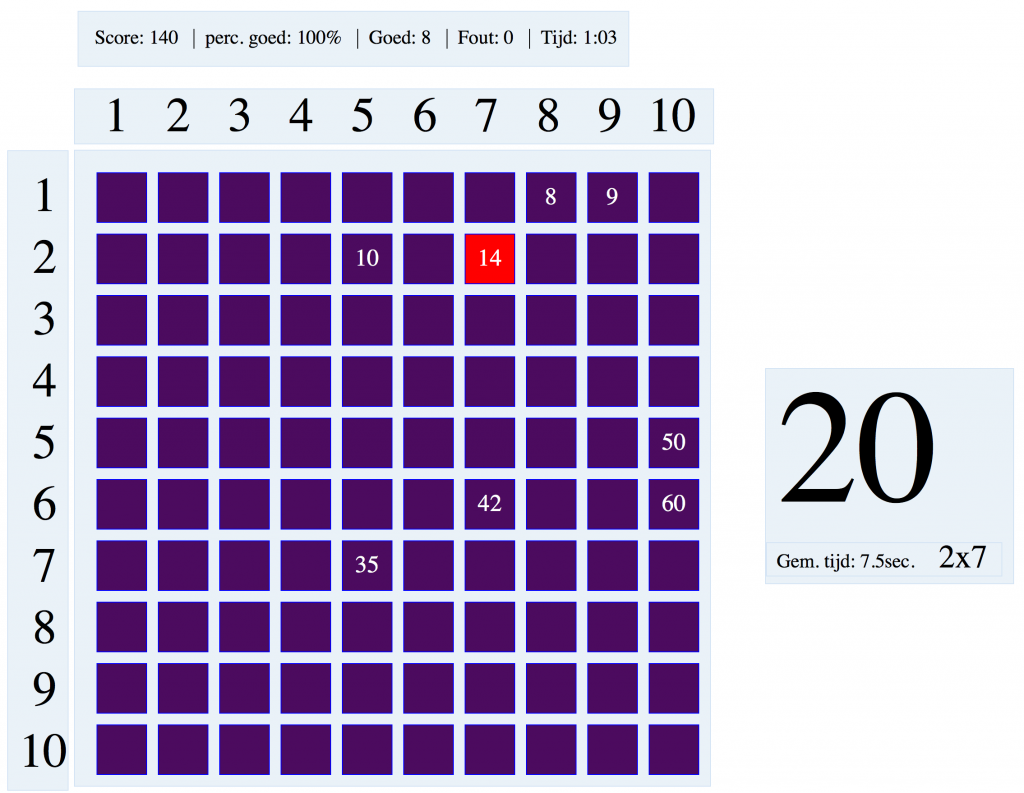

I work at a school for vocational education. In this school there is a department where we (students and teachers) are building resources to learn from. A few months ago we build this exercise:

All the timetables are there and the exercise is counting your mistakes and keeps track of the amount of time you need to finish to finish them all. You have to correct every mistake before you can continue. The record right now is at 4 minutes and 37 seconds and it is in the hands of a fanatic colleague.

The first time the 12 year old tried this exercise it took him 15 minutes with a lot of mistakes. He didn’t work on it with a lot of focus. He didn’t really want to do it and he probably thought that it was not possible to get any better at and that he had reached his potential. His mom gave him a “high expectation” to do it in less than 8 minutes within a week. He had to do the exercise at least once a day and keep track of the results.

A week later on a Friday morning I received an app. He finished the exercise in 7:43 with only 6 mistakes. He was proud. Two of my colleagues and some students decided to try and beat his score which was pretty tough. They did not get his results the first time. We apped the scores back to him. In the end there was only one colleague who was faster. And then we received another app from the boy’s mum that her son kept at it and was now finishing in 6:49 minutes with only 4 mistakes. His mother told us the boy was jumping with excitement. He doesn’t have dyscalculia. He just needed to find his focus and put in the effort.

Somewhere between this first attempt and him beating the 7 minutes mark we looked at the numbers he had problems with, where he made mistakes or which took him a long time. They were 32, 54, 56, 63 and 64. Strangely enough almost everybody trying this exercise runs into problems with these numbers. Which multiplication leads to 56? Do you know? We trained on those numbers and eventually that led to 6:49 with only 4 mistakes. This is deliberate practise. Analyse the things that you are not good at and specifically train on those.

We ask almost everybody who comes here to do this exercise and it is surprising what is happening. Almost everybody tells us that some sort of anxiety arises, a sort of extra focus. I think this is partly because others know you are doing this exercise and because of the clock and the counting of your mistakes. You’re competing with others but also yourself. You really want to make as less mistakes as possible in as little time as possible. And I have heard several colleagues curse when they made a mistake or when they got stuck on a number. A lot of people started over again and again.

I also think that our brains are trying to find a strategy to finish this as fast and as accurate as possible. I noticed that the first time I did the easiest sums (1×9 instead of 3×3 – 1×20 instead of 5×4) and that I tried to fill squares close to each other to keep the board as clear and organized as possible. And the brains think of using a mouse instead of the track pad. My colleague told me his brains divide the numbers. With numbers below 50 he looks at the left-top side of the board and above 50 at the right-bottom side. And with a lot of those strategies the brains are working this way without really realising this. Only when asked you realise that you are using and adapting strategies.

A few weeks later I am at a conference about literacy and learning. I tell this story to a German scientist. She is interested and she starts using the exercise. First attempt: 11:43 and 5 mistakes. 1,5 hours later she scores 6:07 with 3 mistakes. She did the exercise 5 times and her “problem numbers” are 32, 54, 56, 63, 64. A few days later she sends another result. She can’t let go. She knows it can be done in 4,5 minutes and so she wants to achieve this.

Automatising timetables isn’t fun. It can be an enormous challenge. But it can be done. The boy saw that he became faster and made less mistakes each time he tried. And that’s what made him realise he wasn’t at his limit. That’s what made him put in the hours that were necessary to automatise timetables. It is all about a challenge and deliberate practice. The program with the fast feedback gave the boy a very effective opportunity to train and the possibility to see the progress. Perhaps most important, the boy started to believe that it was possible. And that’s what is worrying. The label dyscalculia might just have the effect that it crushes the believe that it is possible.

In the meantime the German scientist went on. She now has the record. She scored 4:21 with 0 mistakes. Can you beat that?

The record is now 2:02 with 0 mistakes… And you can download the program for free as an app if you have an IPad.